This article is copyrighted.

Please credit the web site and author as your source when using material.

Brehme's Picturesque Mexico

Spanish Version: "El México pintoresco de Brehme"

Around 1905 a young German photographer named Hugo Brehme (1882-1954) made his way to Mexico to photograph this fascinating and complex country. Although in his twenties, he already had mastered his expensive photographic equipment and had developed an artistic eye trained by photographic studies in Germany.

Taking pictures of the people and places of Mexico soon became his life’s work and to this day, his work attracts fascinated interest from artists, photographers and collectors worldwide.

Brehme would live in and travel around Mexico for almost all of his life. He even became a Mexican citizen shortly before his death. While Mexico had a strong impact on Brehme, he in turn had a profound influence on generations of Mexican photographers, beginning with Manuel Alvarez Bravo. Recognition of Brehme as one of Mexico’s outstanding photographers came primarily through the thousands of small photographs he took and printed as postcards during his long career.

One hundred years ago, postcard images of foreign lands and peoples filled the insatiable curiosity of less adventurous homebodies who exchanged, collected and pasted millions of postcards into albums. Photographers fanned the globe, including Mexico, to meet the demand in markets abroad. Most of the photographers brought with them preconceptions and prejudices from their homelands. They snapped the pictures they wanted and left. A few stayed, lured by market opportunities within Mexico.

Photographers and publishers with non-Spanish surnames dominated the postcard market during the first two decades of the 20th century. Most of the German, French and Americans set up business in Mexico City, including Bollbrügge, Briquet, Kahlo, Miret, Ruhland & Ahlschier, Scott and Waite. Other foreigners dominated several smaller local markets: Schneider in Chihuahua; Kaiser in Guadalajara and San Luis Potosi; Gossmann in Saltillo, and Neubert in Zacatecas. Companies in the United States published untold numbers of Mexican postcards, many of which were printed in Germany, Switzerland and Austria. Some were produced by photomechanical methods in black and white, but most were colorized. Few of these early cards were real photos.

World War I and Hugo Brehme had a part in changing all that. Because of the war, postcards were no longer printed in Europe and shipped for sale in North America. Hugo Brehme effectively steered the public’s taste away from commercially printed, colorized postcards and toward his handsomely composed real photo postcards of Mexico printed in black and white and sepia tones. Until the mid 20th century, Brehme and a legion of other photographers produced countless numbers of images that today give us a documentary record of Mexico’s rural and urban life.

Brehme’s Photographic Business

Leaving old debates aside about whether photography is an art, Brehme considered himself an artist. As early as 1912, Brehme established a studio at 1a. San Juan de Letran No. 3 in Mexico City, and the earliest postcards bear this address. By 1919, he had opened a studio at Avenida Cinco de Mayo No. 27 and called it “Fotografia Artistica Hugo Brehme”. It was in this studio that Manuel Alvarez Bravo worked and learned the fundamentals of photography, including making postcards that sustained Brehme’s studio financially.

Unusual for a gifted artist, Brehme diversified his business and was an innovative marketing person as well. Sales and services to both residents and tourists helped keep his business afloat. Brehme introduced the photographic Christmas card to Mexico, along with souvenir booklets containing printed views that tourists could remove and mail. He specialized in sales of the German-made Leica camera and he offered full photographic services, including film, developing and enlarging. He advertised that mail orders received “immediate and careful attention.” His photographs and display advertisements appeared in influential tourist guides and magazines, including those by Bernice Goodspeed, Frances Toor and Manuel Toussaint.

Hugo Brehme is the only photographer recommended in the 1927 edition of Terry's Guide to Mexico. Terry states that Brehme had “the largest, most complete and most beautiful collection of artistic photographs (view, types, churches, etc.) in Mexico. Many of them are unique, unlike the ordinary views.” Terry pronounced Brehme’s postcards “the best collection in Mexico at the most reasonable prices.”

Subject Matter

Prime tourist destinations dominate Brehme’s subject matter. Images of Mexico City, Xochimilco and other destinations near the capital account for one-third of all postcards he produced. The volcanoes – Popocatepetl, Ixtaccihuatl and Pico de Orizaba in that order – are the second most commonly found Brehme cards. “Mexican Types,” which were really portraits of persons throughout Mexico, primarily featured tlachiqueros, charros and china poblanas as cultural icons. Despite the immense interest worldwide in Mexican ethnology and archaeology sites and artifacts, they account for only about 10 percent of all Brehme postcards.

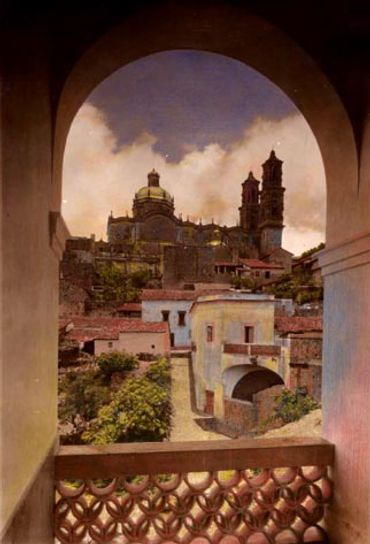

Images from the state of Veracruz outnumber Taxco, Cuernavaca and Puebla, in that order. As Mexico opened up for development and tourist travel, Brehme’s lenses followed the railroad tracks. When highways cut through the mountains, Brehme documented the motels that sprang up alongside them. More postcards have survived from the new tourist stop at Tamazunchale than the much more photogenic Amecameca and Sacromonte! Brehme made only small numbers of postcards of locations scattered throughout the rest of the country. Brehme apparently didn’t venture with his camera near the border with the United States. No Brehme photos of border towns seem to exist. Brehme’s books include only a few shots of Chihuahua and Monterrey, apparently the farthest north he photographed.

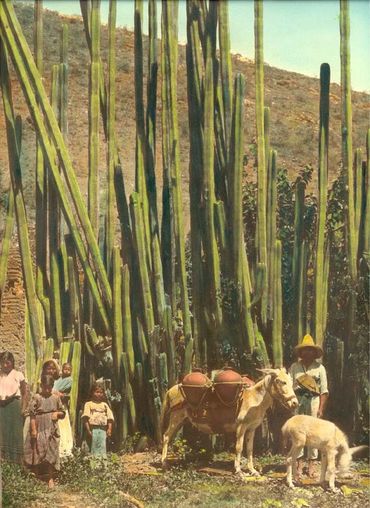

Throughout his published work, Brehme typically treated human figures as props, deliberately posed to achieve balance in the composition or to give a sense of size or perspective. He usually placed human subjects at a distance and seldom shot close-ups. By studying series of postcards taken at the same location and at the same time, we gain insight into how Brehme set up his shots, his method of composing the elements of a scene, and the large differences even slight changes can produce in the making of the original negative and in its printing.

Brehme rarely shows that he is emotionally involved with persons he has photographed. When he does, the effect is striking and reveals the empathy Brehme must have felt for the Mexican people, particularly those who labored hard to make their living. Brehme’s portraits can be expressive and full of life. While he is best known for his scenic landscapes and architectural photographs, he shows in his much less common portraits his less recognized side.

Real Photo Postcards

All of Brehme’s postcards are standard size -- 3-1/2” by 5-1/2”. Postcards in horizontal format outnumber vertical postcards three to one. The vast majority are real photo postcards -- sharply focused, handsomely composed, and richly printed on a variety of photographic papers with a full range of tones and finishes that gave his postcards richness and depth. Brehme often printed the same image in either sepia tones or black and white, and in either glossy or matte finishes. He printed the majority of the early cards on photographic postcard stock made by the German companies Agfa and Gevaert. He also printed on Artura and Kodak Velvet Green papers from the United States, but by World War II, he used papers made by Kodak manufacturing plants in Mexico.

Real photos usually contain the signature, the negative's number, title, and oftentimes the name BREHME. Most of these identifying marks were hand-lettered in the negative. On the more individually done postcards, the very same image can vary in the title line -- different handwriting, different place name, and even the wrong number written on it!

Brehme produced a more commercial series on durable paper stock with postmarks dating from 1923 to 1934. The images are in uniform tones of either brown or gray. The number and title appear in white typeface on the front of the cards, and Brehme’s name and copyright warning appear in blue printing on the back. These postcards appear mass-produced in comparison to Brehme’s real photo postcards that display a wide range of tones and finishes.

Printed Postcards

In addition to his extensive inventory of real photo postcards, Brehme published at least 12 booklets containing postcards with perforations on one side. Tourists tore out the postcards and sent messages with postmarks dating from 1919 to 1929. The dozen booklets all bear the Brehme studio address on Avenida Cinco de Mayo. Each booklet contained either 10 or 12 views printed on sturdy paper in either brown or blue ink, with titles in either block or cursive typeface. Few intact booklets, complete with their identifying covers, have survived.

Brehme also published cards printed by traditional photomechanical methods in monochromatic green, black, or red-brown ink. The lithographer printed the images on acid paper stock that is now deteriorating, an unfortunate circumstance because some of the views in this edition are not found elsewhere. Tearing and edge chipping explain why so few of these fragile cards exist today.

Compare the major types of postcards by clicking below on the four views of the volcanoes Ixtaccihuatl and Popocatepetl:

Dating Postcards

The postmarks in the author’s collection of vintage Brehme postcards range from 1912 to 1951. Cancellations are helpful but do not absolutely determine a postcard’s age because a new cancellation can appear on a much older card. In order to date an image, collectors consider other factors as well. The types of photographic paper and backstamps the Brehme studio used over the years help collectors to establish age.

About 90 percent of Brehme’s cards were real photos. Manufacturers often printed the name of the photographic paper within the box to place postage. For example, if a Brehme card has the name of “ARTURA” paper in a typeface containing serifs, a researcher knows that the card dates no later than 1919. The Artura name without serifs appears on photographic postcard papers made well into the 1920s.

The earliest postcards bear two addresses: Post Office Box 5253 and 1a. San Juan de Letran, No. 3, in Mexico City. Brehme's backstamps reflect the changes of his post office box number over the years and the relocation of his studio from San Juan de Letran to Cinco de Mayo to Madero to Gante. By matching the age of the paper to Brehme’s backstamps, we can approximate how long his studio remained at a particular address.

Maximum Cards

Brehme’s postcards were ideally suited for making “Maximum Cards,” in which the picture on the stamp bears strong resemblance to the picture on the postcard. Considered as novelties or specialties, maximum cards are standard postcards that stamp collectors enhanced and traded with each other worldwide. The hobby was wildly popular in Europe, especially France. The collector “maximized” the stamps by his unique presentation of the stamp to fellow collectors. The collector’s challenge was to place a stamp on the face of a postcard that best illustrated the image on the stamp. The collector then sought the best postmark and other add-ons to enrich the card. The finished product is a harmonious whole, balanced and symmetrical, providing a context and meaning for the stamp.

Maximum cards, particularly those canceled on the first day of the stamp’s issue, are a fruitful area to observe that several Mexican stamps owe their origin to photographs on postcards. Maximum cards are fascinating because they serve as a multicultural bridge between the two most popular hobbies of their day – stamp and postcard collecting – and as a medium for a collector to distinguish himself or herself among millions of others.

Apparently, collectors seldom actually mailed their maximum cards, although they are all artfully postmarked. More likely, the collector placed the maximum card in a protective envelope for trading with a fellow collector. In fact, relatively few postcards in Brehme collections bear postmarks, indicating that purchasers regarded his postcards as photographs worthy of preservation.

Collectors and Copyrights

Collectors in the United States dominate the postcard hobby. The high quality of Mexican cards in general is unrecognized among collectors today. With few exceptions in the real photo market, the work of Hugo Brehme is presently undervalued. Ironically, Brehme has been “lost” among thousands of his own images because of the anonymity inherent in the postcard medium and the fact that his work often has been mistakenly credited to others. Many of the most memorable photographs taken during the Mexican Revolution and previously credited to Casasola were the work of Hugo Brehme. Apparently, no Brehme/Casasola images appeared as vintage postcards. Postcard makers, however, are reproducing the images on modern cards easily recognized as new.

Given the ubiquitous nature of postcards -- their inherent sense of being in the public domain -- Brehme had good reason to place copyright notices on most of his prints before they left his studio. Nonetheless, his work appeared unaccredited in the large format volume Mexican Architecture, published in New York in 1926 by William Helburn. Although the title page reads "Photographs and text by Atlee B. Ayres", at least 31 photographs and postcards published were really the work of Hugo Brehme. Almost all of Brehme’s original photographs are clearly marked "Es Propiedad - Copyright" or “Propiedad Asegurada”, but the publisher ignored not only the Brehme notices but those of other photographers as well. Helburn appropriated the work of Antonio Garduño, J. A. Mullins, the Rochester agency, and Charles B. Waite without credit in Mexican Architecture. No doubt, there are many other instances of Brehme’s original images attributed incorrectly to others, or with no acknowledgement that Hugo Brehme was the photographer. Buyers may easily acquire postcards and use the images for their own purposes.

The End of an Era in Black and White

A collector can find quirky and delightful oddities by studying Brehme’s postcards, especially compared with his photographs published in books. Close viewing reveals such “hidden delights” as a small solitary man standing precariously at the top of the tall water tower, or a man meticulously dressed in a black suit, tie and hat sitting on the ledge of a pyramid, standing near the edge of a volcanic crater, or peering at the camera from behind a wall. Could the man be Brehme himself….an assistant…or son Arno?

Arno Hugo Brehme was born in Mexico in 1914 and he grew up in the photography business. Under the Mexicanized name of Armando Brehme, he submitted for publication his black and white photographs of the eruption of Paricutin in 1943. Large photographs of Paricutin from the Brehme Studio bear penciled signatures on the mat in one of two ways: “Hugo Brehme” (father) or “H. Brehme” (son).

Although the Brehme Studio occasionally hand-tinted its photographs in larger formats, the studio apparently neither colorized its postcards nor printed them from color film. Unlike his father, Arno made the transition to color film. Mark Turok, who pioneered the modern photochrome postcard in Mexico, published four chromes with a photo credit to Arno Brehme. The four views are of a market and archaeological sites in the State of Oaxaca. After Hugo Brehme died in 1954, Arno abandoned his father’s postcard business. Instead, Arno expanded into commercial (advertising) photography.

The advent of photochrome postcards marked the end of Hugo Brehme’s era. Real photo postcards dominated the market for some 30 years, but publishers and printers issued fewer and fewer of them in the second half of the 20th century. Brehme's postcards are scattered worldwide. By preserving them in collections, displaying them in museums, and publishing the vintage images, we continue to see the Mexico that Hugo Brehme saw through his camera lens.

ARTES DE MEXICO, "La Tarjeta Postal" (Numero 48, December 1999)

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.